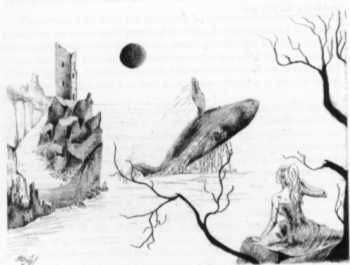

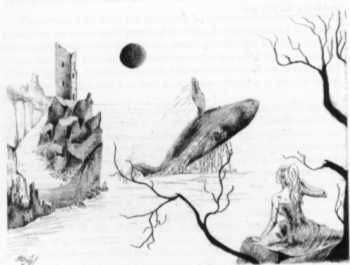

Illustrations by Katrina McLeod

(Boris Books, xvi + 180 pp, $19.95 Australian, ISBN 0 646 16060 5)

Since 1979, the Sea Shepherd has pursued a relentless campaign against the slaughter of sea mammals, including whales, seals and dolphins.

Frankie Seymour sailed on the Sea Shepherd in its hunt for the Russian whaling ship Zvesdney in the Bering Sea, and took part in the subsequent campaign against the killing of dolphins by the Japanese fishermen of Iki Island.

All Hearts in Deck is Frankie's personal account of those two campaigns. It is a marvellous mixture of poetry, old-fashioned adventure on the high seas, and a compelling statement about how compassion and a bit of rage can save the whales and the world.

Here is the first chapter.

In a way this story, like my dreams, begins in a tropical island of the south seas-with the two weeks I spent in Hawaii waiting for the Sea Shepherd to arrive in San Francisco. Those two weeks set the scene for the strangeness and beauty of the whole adventure, and also for many of its frustrations and philosophical dilemmas. Hawaii has since become for me a kind of emotional touchstone or reference point for an experience which both began and ended there, and took me, in between, to a part of the world that could not have been more completely different from it.

Hawaii was on our flight path to San Francisco where we were to join the Ship. Vivienne Smith, a friend of Peter Woof's sister, was travelling with me to join the Sea Shepherd. She had little background in the environmental and animal rights movements, but she had been appalled by Greenpeace media coverage of the slaughter of seals and whales and wanted to do anything she could to stop it. In part, she was also running away to sea. Her Canadian boyfriend, Kerry, whom she had met while he was on a working holiday in Australia, had recently left to continue his world travels, and I think she had some idea of racing him home. Her real name was Wookie-a fact I found singularly entertaining, although she looked nothing like the Star Wars character Chewbacka.

Viv had friends in Hawaii. When we stopped at the airport in Honolulu on the twenty fourth of June 1981, we rang San Francisco to see if the Sea Shepherd had arrived yet-and learnt that the Ship had been delayed in its departure from Alexandria in Virginia and was not expected to reach San Francisco for another two weeks. That meant we could stay with Viv's friends for a fortnight, before travelling on to the USA mainland.

Viv was delighted — but I wasn't so sure. Having finally, after two years of waiting and preparation, got myself en route for the Sea Shepherd, the last thing I wanted was another delay.

But there was nothing else for it. We flew to the island of Hawaii, the largest island of the Hawaiian cluster (called Big Island to distinguish it from the State of Hawaii which includes all the Hawaiian Islands). We rented a hire car, and drove to Waipio Valley, located in the fertile north east of the Big Island.

Waipio has been settled by the Polynesians longer than almost any other part of the Hawaiian Islands, but is almost inaccessible by road. We left the hire car parked at the top (the descent was far too steep for it), and hitched a ride down to the valley in a passing four-wheel-drive, full of sun-tanned American hippies and unusually aromatic marijuana smoke.

The house we sought was at the bottom of the hill, but its owners were out when we arrived. It turned out they had never received Viv's telegram and, of course, they had no telephone. They had no electricity or running water either, for that matter, but managed quite nicely just the same, with kerosene lamps and a fresh water spring bubbling out of the ground in their "backyard". Viv and I fell asleep under a big mango tree, and had recovered from some of our jetlag by the time our hosts, Pam and Doug, got home.

Hawaii was warm, lush and astonishingly beautiful. Our first week there was spent driving around the Big Island, with our hosts showing us the sights-magma tubes like giant worm-holes, velvet seas ruffled by the trade winds, black sand beaches, rainforests, lava deserts, fresh water springs and pools a European dryad would kill for.

Once we snorkelled in a deep, narrow pool, fed by both fresh water springs and sea tunnels, and I spotted about five fathoms down something that seemed to glitter dully against the black rocks. I tried diving for it, but I just couldn't quite get deep enough. I pointed it out to Doug who managed to retrieve it. We brought it up into daylight.

It was a dainty, fourteen carat gold neck chain. Doug clasped it round my neck. I was momentarily blissed by the sheer romance of finding a sunken treasure on a tropic isle of the "South Seas". Then, rather hoping he'd refuse, I told Doug he should keep it because he'd been the one to retrieve it.

"You found it," said Doug, "Keep it as a souvenir of Hawaii."

There was something symbolic in the incident. A devotee of science fiction and fantasy from way back, I had always found Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings reminiscent of our struggle to save the global environment. The march of the Ents in the last defence of the forests. Gandalf's assertion that all living things are his stewardship, and that if any green and healthy thing survives the Darkness his work will not have been wasted. The Ring itself-a power so dangerous it cannot be used for good, even by the good-like nuclear power.

When Deagol found the Ring on the bottom of the Gladden River, Smeagol, his friend, killed him for it. A little gold necklace is obviously no Ring of Doom. But here, on the eve of a genuinely dangerous quest in the defence of life on Earth, Doug and I were sitting by the pool, arguing about who should keep this treasure-in reverse!

In our second week, Pam, Viv and I hiked together up the steep, perilous zigzag trail which leads northwards out of Waipio Valley, and across another eight miles, comprising fourteen ridges and gulches, to the wild, unsettled valley beyond.

Our first night on the heights between Waipio and Waimanu was pleasant. Copious quantities of vodka and tomato juice kept the cold away. But our second night on the ridges, in the little two-wall shelter which stood half-way between the two valleys was the coldest night of my life, colder than any night I subsequently spent in the Bering Sea, the Canadian Rocky Mountains or Newfoundland. The problem was, of course, we hadn't carried tents or sleeping bags — in Waimanu we wouldn't need them. We'd forgotten about the two nights we'd planned to spend on the ridges.

Too cold to sleep, I got up in the hour before dawn and made a fire outside the shelter, and watched the glowing, intelligent eyes of wild pigs catch the firelight in the forest. They were shrewd and quiet, and watched me with the same steady wariness with which I watched them.

In the morning we were joined in the shelter by a hunter on his way to "shoot pig" for the fourth of July luau. He leaned his gun against the wall of the shelter, where I could have grabbed it and run, and disposed of it in a pool beneath a nearby waterfall.

But I was a guest here. This hunter was a friend of my hosts, and he was behaving in a way that both he and my hosts considered quite proper and appropriate. Pigs, after all, were brought to Hawaii by the Polynesians as a food crop — along with all the fruit trees. Their numbers had to be controlled, somehow, for their own and everyone else's good-the usual arguments. At least these pigs weren't tortured in factory farms and terrified in abattoirs before they died.

So I left the gun leaning there, and tried not to look at it. It was one of the greatest acts of self-discipline I have ever accomplished. And I simply don't know if it was right. I don't imagine the pig shot with that gun later that day would have thought so.

I took out my guilt and frustration over the gun on a couple of rat-traps someone had left baited in the shelter. I attacked them with the screwdriver on my Swiss Army knife, and scattered the twisted bits around the forest.

The tensions of the day did not end there.

By nine in the morning, hiking was hot as hell. We stopped by a deep pool under a waterfall for breakfast, and noticed through the shadows of the pool, huge claws in motion on the rock shelves. "Yabbies!"Viv shouted with glee. "Let's catch one for breakfast!"

"Get a rat up you!" I responded, more with shock than intentional vulgarity or conscious speciesism. I dived into the pool, scaring all the yabbies home to their grottos. The water was icy.

As I surfaced, squealing with cold (thinking as I did so that squealing is another trait we humans have in common with pigs-and rats), and scrambled out, I observed Viv and Pam in conversation with a small American boy who had arrived by the pool ahead of his bush-walking father.

"There are yabbies in the pool, and they're huge!" Viv was informing him excitedly. The boy looked warily towards the pool. He'd never heard of yabbies, let alone huge ones, and Viv might as well have said there were bunyips in the pool, judging by his reaction.

"Crayfish-fresh water lobsters," I tried to explain.

"Prawns," translated Pam dryly to the boy's obvious relief.

We made a fire and cooked some rice for breakfast. Pam and Viv made no further mention of catching a yabby. They deferred to my sensitivities — but I felt Viv's reproach all day.

In the afternoon we zigzagged down the prickly, pandanus-lined track into Waimanu Valley. On the beach we made our camp, shed our clothes (except for shoes which we would need) and hiked deep into the valley, to the high waterfall and icy pool at the heart and soul of a lost world.

The Polynesians had never settled this valley-too wild and inaccessible even for them. None of the usual Polynesian plants - the mangoes, avocados, guava and papaya that just fell into your hand off the trees of Waipio Valley - grew here. It was like walking through a valley of the Pliocene Age.

Two shots heard far-off indicated that the pig-hunter had found his prey. The magic of the place vanished in the single, sharp, deadly bark of sound. I suggested heading back for the beach before our own naked hides were mistaken for pigskin. After a twilight swim, Pam and Viv went off to the pig-hunters' fire far down the beach to join their luau. I stayed alone at our camp, feeling like party-pooper, and feeling angry that I was allowing myself to feel guilty for such an absurd reason, when the only thing I had any real business feeling guilty about was not disposing of that shooter's gun.

Eating meat, fishing, killing "vermin". Why travel halfway round the world to save animals when such a holocaust of cruelty lies at the heart of our fundamental way of life?

And always the answer came backjust as quickly: because you have to start somewhere, so you start where your heart first leads you-to beings who are as intelligent, as socially and emotionally highly developed as ourselves, and who are near to extinction. And you start where you are most likely to make a difference. A difference for the whales would be a wedge, a beginning of a difference for all the others.

And then, as always when I was alone, I began thinking of home-and thinking of "him".

* * *

The next day we hiked back to Waipio, and that night we had a fully vegetarian feast of local fruits and vegetables, washed down by more vodka and topped off with amazing dope. The next morning we flew to San Francisco, where we spent yet another week waiting again, because the Sea Shepherd still hadn't arrived. We stayed with the family of Denise "Dee" Dowdall, one of Peter's engine crew. Dee's sister, Nancy, was, like me, an avid reader and aspiring writer of science fiction, so we had a ball talking everything from H.G. Wells to Star Trek, from Ayn Rand to Ursula Le Guin.

When the Ship did finally make landfall on the West Coast of the USA, it docked at Los Angeles. Dee flew home to San Francisco to visit her family, and told us that the Sea Shepherd would not be stopping in San Francisco. We would have to fly to Los Angeles instead.

Dee was great fun — another Trekkie. Between Peter and Nancy we'd heard all about her before we met her, and she lived up to their description. When she couldn't get paid work in the environmental field, she generally worked as a movie projectionist, and could tell you the whole plot, cast and budget of just about any movie you could mention. She had worked with Paul Watson on marine mammal issues ten years before in Hawaii, and had joined the Sea Shepherd (II) in Glasgow five months ago in February. Because of her, Viv and I had a good picture of all our shipmates before we joined the Ship.

The night before we flew to Los Angeles, Viv, Dee and I had dinner with Dee's family at a wonderful restaurant on a cliff-top overlooking a wild ocean where great waves pounded high black rocks which rose like teeth from the open sea. In that hour, going to sea to save the whales once again seemed romantic and adventurous, every bit the fantasy of my childhood. Dee's mother commented that it reminded her of the War, not the horror and violence of the War, but the poignancy of watching loved ones go off into danger to do their bit for a cause.

On the fourteenth of July 1981, Viv, Dee and I flew to Los Angeles.

Copyright © Frankie Seymour, 1993